The generational divide in Japanese culture/cinema is a fertile trope for many storytellers. Stories of youth rebelling against adults and the established order, and even posing a very serious and devastating threat, provide the context for films like Akira (1986). The failure of adults to pass the values and responsibility for society is also a central theme to Akira Kurosawa’s King Lear adaptation Ran (1985). There may be no greater film exploring this divide and the inability of the previous generations to bridge that gap than Kinji Fukusaku’s Battle Royale (2000).

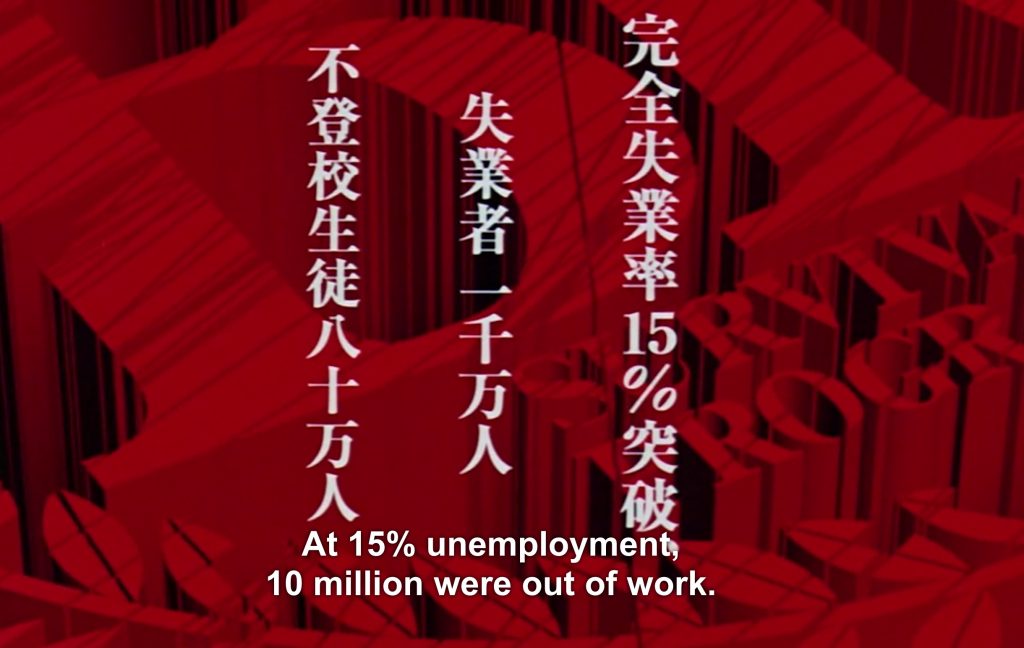

The setting is established using austere titles at the beginning of the film that announce a terrifying situation in Japan where the nation has collapsed and there is a 15% unemployment rate. The students are boycotting school, millions are out of work and fear of the youth lead the government to pass the Millenium Educational Reform Act, aka the “Battle Royale” Act. The games are covered by the media, and are seemingly intended to control the youth, though the students have no conception of the law when they are selected to be the game’s players.

Released as a novel in 1999 and adapted for film in 2000, Battle Royale’s influences can be seen in the concept for the Hunger Games trilogy as well as on Quentin Tarantino, who reveres the film and cast one of its actors as Gogo Yubara in Kill Bill. Nearly prevented from being released in Japan, the extreme plot has its foundations in the experiences of the director Kinji Fukusaku during World War II. In an interview with The Guardian, director Kinji Fukusaku’s recounts his wartime experiences when he was the same age as the high school students in the film:

“I was working in a weapons factory that was a regular target for enemy bombing. During the raids, even though we were friends working together, the only thing we would be thinking of was self-preservation. We would try to get behind each other or beneath dead bodies to avoid the bombs. When the raid was over, we didn’t really blame each other, but it made me understand about the limits of friendship. I also had to clean up all the dead bodies after the bombings. I’m sure those experiences have influenced the way I look at violence.”

Battle Royale is permeated with ire and indignation, both of elders for their children and from the children for their elders. The main character, Shuya Nanahara, is raised by his father after his mother leaves the family until his father’s suicide on the first day of seventh grade. As an orphan that has had his trust betrayed by his parents, his only relationships are with his classmates, though he is haunted by memories of his father’s suicide. Another student’s mother prostitutes her child to a predator while hoping that her daughter is not weak and unable to manage her responsibilities like her.

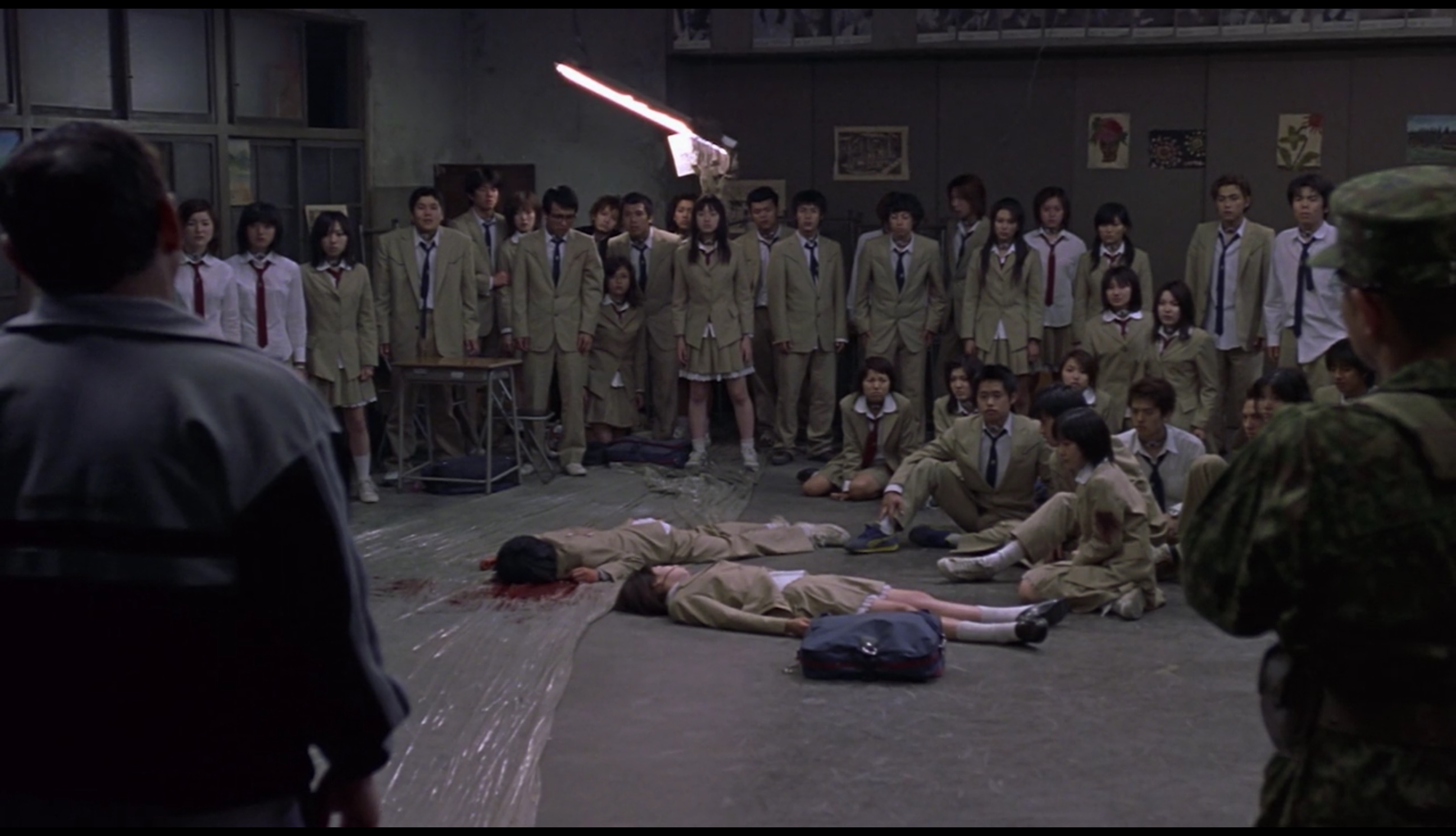

The only adult in the film is played by the famous Japanese actor “Beat” Takeshi Kitano, who plays a former teacher named “Kitano”. Seen at the beginning of the film being stabbed by one student in the leg, Kitano returns as the students learn of their selection in the annual Battle Royale and relishes the terrible fortune of his former students. He mocks them, and advises them not to become “an adult” like their current teacher, who is shot dead for opposing their selection for the Battle Royale.

In this scene, we first see the characters interact with an adult, and the dramatic corpse-strewn gulf that separates them. Kitano feigns disappointment in the students, but tells them “the country is now good for nothing,” and kills two students for their insubordination when telling them about the rules of the game. This scene is critical for displaying the transition of the established adult authority (teachers, military) to a culture of fear from a shame society. It does not matter that the kids don’t fear the Battle Royale Act or its consequences, and they are not ashamed of their ignorance; society fears the youth and is using them as pawns to fight a murderous game in an attempt to exert control. Fear and danger form the foundation of the game, and if the students don’t obey and play the game, they will be killed by the government anyway.

The progression from disregarded teacher/authority figure Kitano, whose class the students mockingly won’t attend and is stabbed by one orphaned student, to feared despot demonstrates this degeneration. The threat of Kitano is established by his casual murder of two students and cheerful updates of the death toll, which is regularly broadcast across the island site as he mocking reads off the list of “goners”. While initially the teacher was dejected by his class’s lack of respect for school and him, he has become an enthusiastic participant of the game and even brings gifts to the students he likes, who will later aid him in his suicide and put him out of the misery that his adult life has become.

Another student, Shinji Mimura, builds a bomb and hacks the military’s network in an effort to rebel against the military and government while devoting no effort to playing the game. Mimura’s uncle, a soldier of fortune, taught him bomb-making and provided other military instruction and is seen as a positive force in young Mimura’s life. Similarly, one of the transfer students absurdly credits his surgeon/fisherman/polymath father for having given him every skill needed to protect himself or others, demonstrating that adults do have valuable information to give to the younger generation, but are incapable of providing them with a functional society or performing their parental roles.

The film’s absurdity and dark humor wonderfully underpin the ridiculous plot and make it more palatable. The concept for the film has inspired so many other stories, though it is the central Japanese themes, dark humor and ridiculous teenage melodrama that distinguish it from the flavorless repeats that followed. It is a great choice for kickstarting this series of 21st century films, both for its release date in 2000 and for its depiction of a new world, born from the calamity of the previous one and desperate to build a better one.